|

Guest post by B. Lynn Goodwin What To Consider Before Submitting to Writing ContestsYou polish your writing, imagining your audience. You read it over. Out loud. Does it say exactly what you want it to say? You have a friend read it to you. Impressed, she says, “You should submit this to contests. Get some recognition for your work.” Maybe you leap at the idea. Maybe you hesitate. Contests make you feel vulnerable. Besides, there’s almost always a fee and nothing’s guaranteed. Perks of Entering a ContestPlacing in a writing contest is a huge boost to your work, though. Acceptances matter. Here are some other perks you might get:

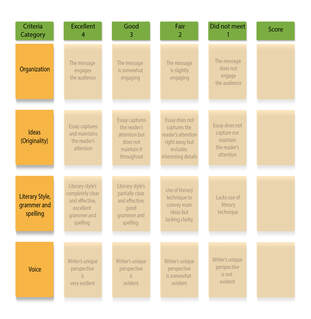

What Do Judges Look For?Without a rubric, judges look for writing that works, ideas that seem original, and something that touches their hearts. They look for carefully edited pieces free of mechanical glitches and work that either says something new or says something traditional in a new way. Instead of writing a traditional rubric as a contest administrator, I’ve sent the questions below for judges to consider. Put on your editor’s hat and answer them before you send your work.

Looking for a starting place? Take a look at the current contest on Writer Advice, www.writeradvice.com. Research other contests and opportunities by Googling contests + (your genre). Questions? It’s easy to reach me through the contact box at www.writeradvice.com.

24 Comments

Guest post by Eve Taft When I was a child, I judged a story by how much I loved its world, and I judged its world by how much I could envision beyond the book itself. I knew there was much more to Narnia than I saw, plenty of glens of the Hundred Acre Woods that didn’t grace Milne’s pages, hundreds of hobbit-holes we never visited. The worlds I loved were complete, with story existing in them, rather than cheap set dressing with nothing solid behind it. Now that I’m an adult with education in creative writing…I think the same thing. One of the main attractions for readers (and writers, let’s be real) of high fantasy is the worlds we get to visit. We love vacationing to Westeros and Earthsea, to galaxies far, far away. And I enjoy creating worlds to escape into, so here’s my take on how to do it well, to make a setting that readers assume goes beyond your pages and love enough to write fanfiction about. What follows is my basic philosophy of world-building and some categories you may want to think about. The short version is this: ask questions, and the answers will build your setting. Start here: forget everything you know. Don’t take earth things for granted—you’re not in Kansas anymore. Keep some basics about how people and societies work: humans survive, bond, interact with their environment, and create. Most of all, people affect each other, in direct or indirect ways. Humans or elves or whatever creatures you’re writing about do the same thing in fantasy worlds. Their geographies, histories, and evolutionary biology will evolve from and impact upon their surroundings, as ours do. And here’s where you get wiggle room, as much or as little as you’d like. Concepts that are cemented into our society (anything from currency to the fact that humans generally live above ground) aren’t necessarily present in your world. You get to play god here. And it’d be a shame to throw such an opportunity away by simply tossing your characters into a medieval setting and choosing a Latin-language-based magic system because it’s worked for so many other people and you’re not confident enough to come up with something new. Which isn’t to say “done before” means bad. Everything has, to some degree, been done before. I’m just saying, keep your options open. BasicsThink about the first things you learn when you’re a child, then ask if those things are true. Is the world round? This doesn’t have to be the case, as evidenced in Discworld and Narnia. Follow-up questions: how do day and night work? What is the configuration of sun(s), moon(s), and stars? This also informs how time works: do your characters have 24-hour days, 365-day years with four seasons? George R.R. Martin does some interesting stuff with seasons, as, I hear, does N.K. Jemisin, though The Fifth Season is still on my TBR pile. So does Hello From the Magic Tavern, a podcast I love so much I’m going to mention it, even though it’s not technically high fantasy because the characters bop back to earth occasionally. Once you have a planet (or loose interpretation of one), what’s your map like? How much of the world exists in your characters’ knowledge? I’m terrible at drawing, but there’s some nifty programs like Inkarnate to help, and if you’re cool enough to draw your own maps, then so much the better. What kinds of resources do different countries/cities have? Who provides what for who, and how does that impact wealth and power structures? (This can also be an opportunity to create interesting class systems for your characters to contend with.) You’ve got a world. Who lives there? Is your main character (start there) human? If the answer is “no” or “sorta,” then invariably, they’re going to be acting as foils for humanity. We can’t get too far away from ourselves. Still, non-human characters give you a lot of leeway as far as cool biology stuff goes, so explore that in depth. Do your guys have two hearts like Timelords? How do they age? If humans are at all involved, what does being human mean in this world? What other species are there, and is there any sort of hierarchy? Who can talk, who is sentient, who is in charge of who, who domesticates who, who has what kind of powers? If you go for any reliable, public domain fantasy races like elves, dwarves, or goblins, think through all these questions for them, too. Elves don’t have to be sophisticated beings with long lifespans, and dwarves don’t have to like booze and gold above all else. Try sticking your orcs in trees or your elves in the ocean and see how they do. But creating the stage and the players is only step one. Once you have a world—unless you’re writing a creation myth—things will have happened in it, and that will inform a lot of what’s going on now. Thus bringing us to section two…. History and AnthropologyRemember “History of Japan?” Well, that guy (Bill Wurtz) made one for the world. You could do worse than watching it and sketching up something similar for your own setting. This should generate more questions that inform your world. You’ll get to economics and politics here: who governs whom, and how? Have economics systems like capitalism, communism, or socialism taken root? What needs do these societies have, and how do they fulfill them? How do your characters perceive demographic information, such as ethnicity, sex, age, or gender? How do these perceptions vary from place to place and culture to culture? What about traditions that humans have evolved like family and societal structures? Do humans monogamously pair-bond, as we seem to have found evolutionarily adaptive here on earth? What kinds of sexualities do people present, and are there rules around them tied to legality or religion? Many of us, myself included, are from a nuclear family structure in a society where heterosexual monogamy is the norm. This has largely been the case in the western world since the rise of Christianity, and if you’d asked me ten years ago, I’d probably have said “Well, seems like that’s human nature, I guess.” However, looking at, say, ancient Roman society, we often see same-sex pair bonding in addition to or instead of heterosexual bonding. And they would have said the same thing: “That’s probably just human nature.” Human nature, whatever that is, is linked to what society wants, needs, and demands. Decide what the norms are for your world, and then, for a good time, make your characters buck them. These questions might be difficult or uncomfortable to sit with and answer. They might reveal the arbitrary nature of concepts we accept as basic truths. This is the heart of why imaginative fiction is so important: it makes us ask what could be. Technology and ScienceThis is where a lot of writers follow the beaten path and give their characters access to roughly medieval-Europe levels of technology, usually kept quite separate from the magic system. There are a lot more options, including melding magic, tech, and biology together. Something I’ve found helpful is to look at various contexts: does my society have the achievements of, say, 1920s London? Are we working with late-stage Inca Empire tech? You don’t have to make your characters literally reinvent the wheel, but where they’re at scientifically is totally up to you. Other places to look for inspiration include various kinds of -punk (steampunk, cyberpunk, dieselpunk, solarpunk). Here are a few big events and inventions that have shaped our current civilization (this is by no means a complete list). They can be good jumping-off points for events that may or may not have happened in your world. Discovery of fire The Agricultural Revolution Invention of the wheel Numerals, particularly the Arabic numeral system, and along with them, mathematics Running water, sewage systems, irrigation Contraceptive technology Colonization The printing press Electricity The Industrial Revolution Antibiotics Nuclear power The internet Climate change and the effects thereof The invention and mainstream adoption of social media MagicYou generally make your magic system out of the whole cloth. Magic systems need rules, a power source, and limitations. Can everyone learn magic, or is it an innate trait? If everyone can, why hasn’t everyone (unless they have)? If your characters are magical, and they have a problem, you should always be able to answer the question: “Why can’t they just solve it with magic?” Different authors manage their magic in different ways. The Inheritance Cycle keeps its magic from being OP by basing it on a fundamental exchange: the energy it takes to do something leaves your body, whether you use magic or do it manually. Lifting five pounds always equals lifting five pounds. Proximity also matters. In Earthsea, LeGuin’s wizards use the “true names” of things to gain power over them, which takes study. Harry Potter characters can’t make food out of nothing or bring people back from the dead, and magic takes concentration and know-how. Dungeons and Dragons wizards have spell slots. Make a system, give it cool shit, give your cool shit limits. And a word to the wise: everyone loves a good loophole. SpiritualityReligions exist to answer questions. The most basic of these questions are 1. How did we get here? and 2. What happens when we die? Unless your setting has found concrete answers to these questions, they’ve probably come up with some sort of philosophy. Actually, depending on how large your world is, they’ve probably come up with several. What they’ve come up with is probably pretty important, as religion often guides a society’s values and taboos. And, unless you have nice, docile, agreeable characters (what’s that like?), throughout history, these religions have changed, splintered off, fought each other, melded each other’s traditions, evolved, and generally gone all over the place. Religions have mythos, day-to-day rituals, rites of passage (birth, coming-of-age, death, etc.). Religious people have varying levels of devotion. Religious organizations have varying levels of corruption, power, and relevance. These are all things to consider. If you’re not interested in coming up with religion, your characters can be lapsed Fantasy-Catholics or Agnostics, but chances are, they’ve interacted with religion in some shape or form. If your novel is an allegory for a particular faith, fantasy is a great vehicle to do this, but it’s pretty rude to caricature another faith as your bad guys and being preachy is a surefire way to get your book put down. Handle fables like this with care: they can be done well if you have a good grasp of subtlety. What Next?Okay, you’ve created this amazing setting, and everyone absolutely has to hear about it, from the magic system to the national anthem of your character’s home country. Right? Unfortunately, no. You do not want to spend the first ten pages of your novel painstakingly explaining all of this. Well, you do, but readers don’t. The absolute worst part of world-building is leaving most of it in your head and letting it come out naturally as you write. In order to head off the desire to just write a visitor’s guide to your setting, you’re going to need to tell someone about it. Get a friend who’s into this kind of thing and talk their ear off. Explain everything (and, if they’re a writer, let them return the favor once in a while. If they’re not, buy them a pizza or something), get it all out of your system. An added bonus is that they’ll probably poke holes and ask questions and make the world better. Even if they don’t, once you finish talking, you’ll have let your creation out into the world to breathe. Then start writing. When you need to explain things, explain them. Decide what your characters and narrator(s) know and what they’d think to explain. Weave in details readers need subtly—this is a fiction novel, not an encyclopedia (although, if you get enough traction, you might get to write one a la A World of Ice and Fire, which I can only imagine is a delightful process). If you know your world, then chances are, you’ll intuitively bring in what you need. Overexplaining typically happens when you’re not sure of yourself, rather than when you’re confident. Have a little faith in yourself and your setting. And, if all this seems like way too much work, then rest assured: there’s a premade world all around us you can write about, and that one’s pretty interesting too.

Guest post by Savannah Cordova One of the great things about storytelling is the ability to create brand-new characters, complete with their own fascinating traits and backstories! That said, no matter how unique your characters are, they’ll inevitably fall into certain categories. A particularly common character type we see is the dynamic character. This is someone who learns some kind of lesson over the course of the story, changing in one way or another as a result. Main characters are usually well-rounded dynamic characters; their evolution is often what drives the story, and readers enjoy being along for the ride. But what about those characters who don’t change? They don’t learn any lessons, they don’t fix any glaring flaws, and they presumably carry on — business as usual — after the story ends. Do static characters have any place in your book? Dynamic characters go on a life-changing journeyWe know that dynamic characters have to change somehow throughout the story, but what does that really mean? Well, a good dynamic character will often realize they want or need something that they don’t already have, and their journey to obtain it will move the story along. Take the Beast from Beauty and the Beast, for example. He starts the fairytale very set in his ways, wanting only solitude in which to languish. He believes his appearance stops anyone from getting to know him, and he’s doomed to live out his days alone. Belle stumbles into his life by chance, and at first, his bitterness and temper prevent them from being anything but enemies. But as the story progresses, Belle teaches him the joys of companionship and love, and the Beast gradually becomes less guarded. He learns to have fun and enjoy the company of another person — and to think of someone other than himself. By the end, he’s changed his mind on how the world works, and his faith in love has blossomed. The Beast is a great example of a dynamic character because he slowly transitions throughout his story, piece by piece. Looking back, we’re almost shocked by the stark difference between the Beast we meet at the start and the one we see at the end (and not only in his appearance!). In any story, a dynamic character is one who has an experience that teaches them something, and they act on that lesson — the action being the important part here. Indeed, if Belle had taught the Beast how to love but he forced his feelings down and kept to his lonely ways, we wouldn’t see much of a shift in him. Readers want to see characters change (for better or worse)You know the saying “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink”? A dynamic character drinks. Without dynamic characters in a story, there simply wouldn’t be much to invest in. Readers want to see change in a narrative — and though the vast majority of protagonists experience positive growth, characters who change for the worse can be just as interesting. Walter White of Breaking Bad is a great example of such a dynamic character. He starts out as a regular science teacher, but turns to the life of crime to pay for his lung cancer treatments. The novelty of this makes not only for a strong character arc, but for a fantastic story; after all, we probably all know a science teacher in real life, but we don’t all know a science teacher who started cooking meth to survive in a country without free healthcare. Of course, the most intriguing part of Walter’s story is the moral shift that accompanies his transition from science teacher to meth dealer. While it might not be something your average reader would see in their own life, it’s easy to imagine how extreme circumstances could alter someone’s principles so drastically. Depicting this kind of change makes your characters feel much more realistic and engaging — even if the dynamic character ends up being pretty unlikable, as Walt does, it’s much better than if they’d never changed at all. And remember that your protagonist doesn’t have to be the only dynamic character around! Giving your antagonist a shift in how they see the world adds a lot of depth to your story. Modern readers are looking for nuance in the books they pick up, so rather than sticking to a static villain in your next piece, play around with giving your antagonist a chance to change… again, whether for better or worse. Static characters fill in the cast—and contrast with the heroWhile our dynamic characters are out there changing their lives, our static characters show zero growth as the story progresses. They have a set of morals or beliefs that they don’t feel the need to change. A static character looks the same from page one to page one-hundred and beyond. If we’ve already concluded that dynamic characters are the most interesting to read about, what’s the point of using static characters in a book? One reason is that stories need more characters than just the protagonist — and if every character underwent some big change, the story would lose focus. If a reader is presented with too many ongoing, life-changing story arcs, the story starts to muddy up. Let’s look back at Beauty and the Beast. There are quite a few static characters in this tale. The blonde Bimbettes only want attention from Gaston, and Gaston is a player who wants what he can’t have. If we had to watch the Bimbettes learn a lesson about inner beauty and Gaston learn one about treating women with respect, we would care less about Belle and the Beast’s story. Another reason to include static characters is for meaningful contrast with your main character(s) — in Beauty and the Beast, the static characters are also used as foils. The blonde trio of Belle’s provincial town demonstrate Belle’s well-roundedness, and how she wants more out of life than to marry Gaston. Gaston, meanwhile, is handsome on the outside but ugly on the inside, superficial and misogynistic, and he stays that way — ultimately serving as the Beast’s polar opposite. Using static characters like this makes us like our dynamic characters even more! Occasionally, “static” main characters represent strong idealsThere’s one more less-common reason to include a static character in your story: if you want an extremely dependable protagonist, often in the context of a chaotic or unjust world, a seemingly static character will do. Take Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games for example. She starts the story strong-willed and set in her morals. She believes in the people, and she is loyal to her friends and family. By the end of her participation in the Hunger Games, these are still Katniss’s key traits. She doesn’t let the Games get the best of her and crack her morals — in fact, her beliefs only seem to strengthen as she’s put through the worst the dystopian world has to offer. But while Katniss’s beliefs may not change, the amount she believes in them does. Her dynamism is in not how she views the world, but in how strong her views are. So while she might seem static on the surface, she’s actually a dynamic character in her own right — just in a subtler way than you’d see with most protagonists. Overall, it’s important to take a look at your cast of characters and determine who the story is really about. Often, that will tell you who your dynamic characters are. How can your static characters support (or get in the way of) your dynamic characters? What is the relationship between these two character types? Having considered this, you’ll be well on your way to a perfectly balanced cast — and a story that readers won’t soon forget.

Guest post by Randy A. Gerritse This simple statement, which eventually became the title of my first ever poetry book after spending over a year writing daily poetry prompts on Twitter for the #vsspoem hashtag, may not be what it seems. This is not a conclusion, an endpoint. If anything, it signaled the start of my personal journey, a first stepping stone if you will to learning the craft of prose. My first thoughts on the essence of poetry were on what it is not—that is, what it’s not to me, born from my early frustration with the most widespread form of poetic expression—forced structures of rhymes, connecting every other line in subjects mostly related to love. I felt that there had to be more to this poetry thing. In certain ways, I still do. You see, I’ve always been a watcher on the sidelines, trying to make sense of the world and its many moving parts, fascinated by the little things that people seem to think that matter, and the big things they dismiss without a second thought. I have always studied patterns of expression and behavior. They intrigue me. As a species, we seem to love these recognizable templates of identity, of communication, of, well, everything. Just pick a form and fill in the blanks—voila, that’s you. Or at least, so the world always seemed to me, call me a cynic. Today, roughly three years into my poetry journey of discovery of both my inner and outer realities, through even deeper than my usual levels of observation and introspection, what I’ve learned is that this thing we call poetry is highly personal. It is the expression of a moment, a feeling, an observation, in naught but words. It is the art to convey what these most human of time capsules meant to the narrator at their moment of conception, to an unknown future reader—more often than not, a future self. Where I am now in my journey, is far from where I started. If I look back at my earliest work—still devoid of any punctuation—I see someone who I barely recognize, and not just in the choice of subject matter. My style of writing is still highly lyrical, but over the years my patterns have shifted, reflecting my changing insights and the changes in my everyday reality. My early work, by a self who despised simple rhymes, despite their already distinct rhythms, these poems are riddled with cliches and naive preconceptions—shifted truths no longer my own. Often these writings feel disconnected to me now and could perhaps have used a little more rhyme to bind them into something more coherent to anyone but my past self. It’s funny how we grow, isn’t it? Let me state this as clear as I can. Do not let anyone—not even me— ever tell you, what poetry is, or should be, for none but you can see inside your soul, your thoughts. If you feel your expression works best using a meter or a rhyming scheme? Go for it. If you think best in Haiku or Tanka? Five-seven-five the hell out of those thoughts and feelings. There is no right way, nor a wrong way. What there is though? Lots of poetic arrogance. Where it comes to poetry, write for you, and only you. Go ahead and share those words, light up the world with your uniqueness, but do it for you—not glory in the eyes of others. Even the masters never found that in their lifetime. Cynics though, trolls and critics, those are ever-present, maybe more these days than in any other age before, ever but a click away. For me, that first statement that became my first book still rings true, be it partly. The part about finding the rhythm, the living heartbeat of existence. I’ve since written many metered works, yet my poems and stories rarely follow conventional paths, for my truth follows a different rhythm than most. It always has. But that is my truth, and there are many. Find yours, it might set you free—I know it did so for me.

Guest post by Rita Henuber Humans can detect over ten thousand different odors. Our scent receptors are capable of smelling a piece of clothing and determining if it was worm by a male or female. Nothing conjures memory more than smell. Scent is a memory bomb trigger. Memories elicit emotions and we want to deliver emotions in our writing. Using smell effectively is not as easy as using other senses. We provide details, mapping out other senses. When we see something, we can be descriptive using visual adjectives like red, blue, bright, big, and so on. For touch we can examine textures—a damp, thick Fisherman’s Sweater with fish scales here and there. Describe the crispness of the hair on a lover’s chest. (That would be the guy BTW.) That feeling when someone gently touches your hair and you’re home alone. As the author you relay to the reader what everything tastes like. Sweet, salty, sour. Bitter. Pepper hot. But who can map out a smell? It’s nearly impossible to describe a scent to someone who hasn’t been exposed to it. As with the name of this blog, Orange Blossom. The very words conjure heavenly scents drifting for miles in spring to those native to Florida. To convey the scent, I can’t gift a reader with a bottle of orange blossom perfume. I use words such as smoky, floral, fruity, sweet, we are describing smells in terms of other things (smoke, flowers, fruit, sugar). Describe how smells make us feel—disgusting, intoxicating, sickening, pleasurable, delightful hypnotic— use of word pictures bring out a reader’s emotional response. “Eww. You stink.” Or “Eww. Get away. You smell like my brother.” It’s more describing how the smell makes you/your character feel. Again, what we want in our writing. Smell is the most evocative sense. Pheromones are nature’s romantic calling card. Writers rely on it to increase intimacy between heroes and heroines. Studies have been done proving women are more attracted to men who smell the least like their own genetic codes. Women were given men’s sweaty, stinky t-shirts and asked which they liked best. I dunno, maybe it was an early Bachelorette show. Anyhow, they found their brothers and fathers shirts to be the worst smelling. When you use the sense description make it applicable to the character. A truck driver is more likely to describe senses in the way he experiences them. “Dinner smells like burning tires.” In the movie Apocalypse Now, Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) is often quoted as saying, “I love the smell of napalm.” That alone, taken in context of the movie is intense. But the quote is not complete. It reads: “Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. You know, one time we had a hill bombed, for 12 hours. When it was all over, I walked up. We didn't find one of 'em, not one stinkin'; body. The smell, you know that gasoline smell? The whole hill. Smelled like... victory." That is chilling. It nods to the horrors of war that the character faces, and the way it’s warped Kilgore. If you think using smell isn’t important in your stories consider we can’t taste until we put things into our mouths. Can’t see if our eyes are covered. Can’t experience touch unless we make contact with someone or something. Can’t hear if our eyes are covered. We always smell with every breath. Always. If you cover your nose to stop smelling, you will die. So, yeah, I think using scent in a story is important. What do you think?

Having the correct pacing in action scenes is essential. Otherwise your big moment will flop and the worst thing will happen: your reader will be disappointed. Fast pacing is a combination of five factors. Read on to find out what they are! Factor One: Time Manipulation The scene itself is usually only a matter of minutes or sometimes even seconds. Think about when Harry and Voldemort clash wands. That was maybe two minutes? But the scene isn’t written like this: Harry and Voldemort pointed wands at each other. The wands blew up. Writing actions scenes requires the author to slow down the clock and stretch out the moment, giving it weight in the plot. This amps up the tension and the interest for the reader. Another way to manipulate time in action scenes is to try and introduce a “ticking clock.” Yes, this could mean a literal timer before something explodes, but it could also be an imminent consequence if something doesn’t happen within the time frame. Someone or something is coming. Something is falling down. Anything that puts an element of time pressure into the scene. Factor Two: Including Action + Reaction We want to give the scene a physical and an emotional punch, a one-two combo. Start with breaking down the scene into smaller actions. What exactly is the character doing? Each motion has more gravitas in this scene so be sure to highlight the actions that are propelling the character forward in the plot. (example: opens the door, feet brush on the rug, a noise comes from the bedroom…) Next, add in the character’s internal reactions and thoughts. (example: no one is supposed to be here) This confrontation is the culmination of more than just one thing and the character’s mind should reflect that. Increasing the emotion for the character also increases the emotion for the reader. It makes them more attached and rooting for the character to succeed. Factor Three: Layers of Conflict Pacing slows down in any scene where there isn’t enough conflict, but it’s especially true during action scenes. Not enough conflict can also make your scene too short or things too easy for your character. The best thing you can do is to absolutely torture your character. Make every single thing that can go wrong happen. If he is about to give a speech in front of a large crowd, make him get a cold the night before. Have him chug a glass of water but not have time to stop in the bathroom. Make him lose all his notes and have his long lost girlfriend in the crowd. Then have a wardrobe malfunction on stage. Remember to include the internal conflict as well. Our speech giver can have a crippling fear of failure from all the years his mother berated him for minor mistakes. Make this action scene so heavy with conflict it is almost too much for the reader to handle. We really want to stress the reader out. That way when the upturn comes, it’s that much more exciting. Factor Four: Zero Fluff. None. Your big action scene isn’t the place for your character to casually notice the surroundings or have long introspections. Anything extra is going to slow down the pace at this critical moment in your story. It could be information you do need to include in your plot, but it’s probably best to save it for another chapter or scene. So if you haven’t explained why the car is able to fly, the big action scene isn’t the right place to tell the whole backstory involving the fairy powder. Be merciless when revising your action scene. Ask yourself if the information is an essential part of the current motion or if it can be moved elsewhere. Cut your sentences down as much as possible. Factor Five: Strategic Structure This is a critical but often overlooked element of writing fast pacing: the visual structure of the words on the page. The reader’s eyes should fly over the text at the same speed as the story pace. Avoid extended paragraphs and complex sentences. Use short sentences deliberately, creating a punch. When you want the reader to pause, say right before the dog is about to attack, that is a good place to put in a paragraph that is a little longer than the others. Look at the structure of the words on your page. Use the visual elements of the text itself to enhance your pacing. Mastering pacing in action scenes takes practice and a focused effort. My best suggestion is to study your favorite action authors and analyze their scenes. How do they use time to create fast pacing? How much of what they write is action versus reaction? What are the layers of conflict? How did they keep the scene lean? What does the structure of the text look like? Studying successful action scenes can help you learn how to build your own. Happy writing!

Layering theme and metaphor in your memoir can take your story from being good to great. The challenge is...well...figuring out what exactly your theme is. The good news? You don’t need to know it before you start writing. In fact, you don’t need to figure it out while you’re drafting either. When you sit down to write your memoir, just get your story down on the page. Finished? Now look over your piece as a whole, whether it is a short memoir or a longer work. Part of your writing journey will be the self-discovery you have when drafting and then stepping back and seeing what came out. Finding Theme in Memoir While reviewing your work, look for patterns in the following things:

When I drafted my award-winning short memoir “Learning to Kick,” I detailed my experience with postpartum depression and identity loss. After reading through what I had gotten down, I noticed a pattern involving my expectations at that point in my life: I kept thinking things would get better and month after month they didn’t. It went on for most of a year until I finally realized I needed to do something, to be proactive in my happiness. I realized this would be the theme of my piece. Using Metaphor to Integrate Theme in Memoir Then it was time to show the readers my theme instead of telling it to them. What was this feeling of things not improving month after month similar to? My mind went immediately to something dark, thinking of light fading away and me drifting further and further from happiness. I also thought about cold and feeling a crushing sensation of sadness. I realized a good parallel would be sinking in cold ocean water.

I wove this metaphor into my storyline in different places throughout: a giant wave knocking me into the water when I found out I was pregnant, dipping just under the surface on my first day alone with the baby, sinking further and further into the cold water as the months progressed. And the moment I realized I needed to fight for my happiness? That’s when I learned to kick, which gave me the title of the piece. Once you see the pattern in your work, think about what it reminds you of in the world. Then integrate this metaphor at key points in your story, including your opening and closing, as well as your title. It will give unity and depth to your piece. It will also do what every writer wants...get your readers more engaged in your story. Happy writing! |

AuthorArielle Haughee is the owner and founder of Orange Blossom Publishing. Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed